This year, has been one of the hardest but also one of the most interesting of my last 10 years as a professional athlete. As many of you who are reading this piece right now, know me as a climber, you’re probably wondering why I put in the title that it’s about being a “pro” in two sports. Well, let me take you on a little journey of the last nine months!

At the end of last year (2018) I decided to pursue a long burning desire to go after a big rock climbing and ultrarunning/long distance challenge. I’d been thinking of the whole concept for a number of years, but honestly, I needed to let the thing really brew in my mind and become so engrained in my psyche that whenever I properly went for it, I’d go all in. And when I mean all in, I mean with every single bit of effort I could muster, all willingness to make the biggest sacrifices and also to put up with a lot of shit if I really needed to.

My face + running = not always amused! (c) Talo Martin

So the challenge – in a nutshell it’s around 88 miles of off-road, trail mountain running (I guess including 30,000+ft of ascent and descent) and 15 multi-pitch routes all soloed – was to do all of this in a single effort enchainment in around the 24hr mark. In a way, I have the climbing covered as I’ve done plenty of that, but running and navigation are most definitely not my professions! If I looked at just the running element of it, I made an approximation that if I could get into perhaps the top 5% of UK fell running standards then maybe I had a chance. Being the optimistic person I am, I gave myself 6 months to go from “park runner” to “ultrarunner” in the mountains and try and do it well.

My first official Ultra – was kind of surprising to win! But also reassuring…

So, what’s it like trying to be a professional climber (and hopefully still continue to be ok at that!) and then also go from almost zero to pretty “full on” in just half a year or so? Is it realistic? Does it impact other things? What’s the reality? I could probably break a lot of this down in thousands and thousands of words – which no doubt you’ll probably be subjected to reading at some point if you read my stuff this winter – but for the moment I’ll try and keep it in broad subject areas and keep it interesting and not too depressing.

Life in General

Right, here’s the nub of it. Running and training takes a lot of time. Climbing and training takes a lot of time. My life outside of these two apparently take quite a lot of time (I have a family and run a few different companies) and apparently the latter doesn’t always appreciate the former. Last year, in the very most approximate sense, I tried to keep my work to 40-60hr weeks and my climbing and training to 20hr weeks. If I was on a climbing trip, this would flip round to 40-60hrs climbing-type activities (cleaning, prepping, redpointing etc) and 20hrs of remote work. To me, this is a pretty enjoyable balance and whilst it’s quite engaging, I absolutely love it in either format. When I then added in 20+hrs of running (some weeks were well over 25hrs when doing 2 x 10hr run at weekend) then things really broke down. I was getting up at dawn to crank in extra training, going for runs at 2 and 3am in the morning and then trying to climb and work on top in the day. Sometimes my drives for weekend trainings that should have been 3hrs were taking 6+hrs as I was having to stop for so many naps. At home, I missed paying bills, I got a load of fines for various things and often I didn’t even make it to bed as I’d fall asleep in random places around the house. On more days that I’d like to admit, I’d experience waves of panic that would wash over me, when I’d think about how much I’d over-committed but I wasn’t prepared to back down. There was no way I could tell any of the people I see on a daily basis that I was going to go easy for a while or drop my sporting expectations just because I’d taken on a big challenge and was suffering. I remember saying to myself that I just needed to put one foot in front of the other and tomorrow would be a different day, no matter how awful I felt on that day. I’m not complaining about this, I’m just explaining what happens when you make these choices…. I don’t have anyone to blame but myself!

Climbing

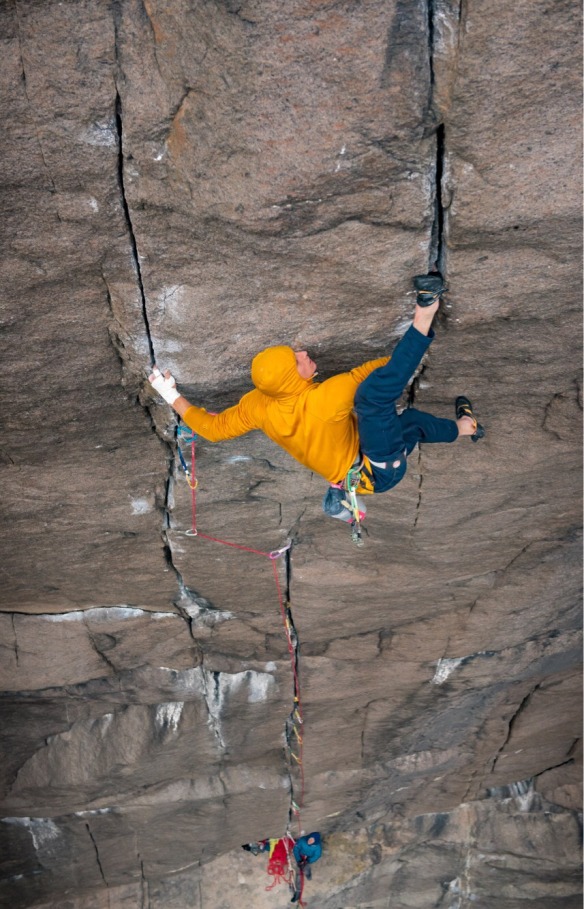

In the first few months, I found that I could climb fairly consistently at the standard I’ve been accustomed to over the last 5-10yrs and around 3-4 months into the ultra-distance training, I was happy to still be climbing and making first ascents on 8b+/8c cracks and my body just about felt normal. Initially, I thought that perhaps I could be superhuman and maybe everyone’s moaning when they say they can’t do everything… (I should have had a word with my future self right then!). As the summer came though, I started to really feel the weight of the cumulative training burden on my body. Each week that came and went, I found it harder and harder to muster up “quality” climbing training sessions and no matter how much I tried to convince myself that a hard fingerboard workout was hard, I knew in my heart that I was only putting a “90% show” on. It was the same when I’d go outside and work on a boulder or route – I’d select to do something that I knew was a touch under my limit. At first I didn’t notice, but once I did, I made the depressing realisation that I didn’t have the motivation to change it anyway. Crap!

By the middle of the summer, I started to feel like I’d lost my top end strength and power, which I had limited amounts of anyway. I’ve always been the type of athlete who can go all day and training endurance is easy, so the last season of consistent loss of strength was alarming. Each month that went by, I kept trying to talk myself into the higher quality sessions, but I just couldn’t suck it up. This was pretty depressing for me, because I feel like I never lack motivation or the ability to suffer, whatever happens. In the end, I chose to accept that my body and my mind were giving me dual message of “F-off Tom, we’re not sticking with you” and I went easy on myself. Man, even writing those words, sounds like I totally wimped out. Did I? Maybe, maybe not.

At least the “rest” holds feel ok! (c) Talo Martin

Running

When I first hit the parks, roads, hills and mountains in earnest in January I was a bit of a punter. I made so many mistakes, that I could keep most of my activities in the “comedy” bracket in my mind. I got lost trip after a trip (and yes I had a map and compass but was rubbish with it) and would run round some of the Lakeland moutains in giant 4hr loops just to realise I was back where I’d started. I tried to run up all the hills and would get burnt out in an hour and then walk and jog for the next six. I took no water or food with me because I thought eating and drinking were for people that don’t like being thirsty or hungry and so if I just dealt with the discomfort I’d save myself loads of weight carrying. Whilst I did find 15-20 miles off-road with loads of ascent did wipe me out in those initial months, I’d just get up the next day and do it again as I don’t mind digging in when necessary. As each week passed, I found I wasn’t really feeling that much fitter or stronger, but I could keep going at a steady pace for long days back to back. Around that same time, I totted up my miles in a week and I realised I’d hit 100, which surprised me.

By the summer and I was getting ready for dry rock and good conditions for attempting links on the main challenge, I started to notice that every time I took 1-2 days of full rest I was getting considerably faster the next time I’d go out. One trip to the Lakes gave me a 7.5hr personal best on a circuit across the fells that had taken 13hrs 2 months before. Another day out, I got 50 miles and around 20,000ft of ascent or so done in 13-ish hrs – the most interesting thing being that the next day I happily went out for a really long run again and didn’t feel too bad. What was so weird about this transition from punter to “pro” was that my lovely gains in running (and they were way better than I expected!) were equally matched by some fairly dismal losses in climbing. No matter how much I told myself that I should just try harder, or have less sleep or make more sacrifices, I couldn’t get my climbing to stay at the top. Even when I read around the subject matter, there was decent evidence to say that a lower limb sport could work in conjunction with an upper limb sport – what was wrong with me?!

Just a few months have started to change my skin chicken legs into slightly more effective chicken legs! (c) Talo Martin

Can you be a pro in both?

I’m going to slightly contradict myself here – or at least on the surface appear to contradict myself. In my opinion, I think it is possible to be at a high “pro” level in two different sports (even in the same year) but realistically it’s insanely hard to be pushing the limits of both of them both at the same time. I just don’t think it’s possible given the physical and mental energy and focus that’s required. I’m absolutely certain that I can keep progressing in both, but they will need to be periodised carefully and if I spend another season of trying to do both at exactly the same time, I’m going to risk breaking or burnout. Loads of my clients ask about this mixture of two sports (normally climbing + running or climbing + MTB) and I stand by answer that if you want to push through your current limits you must pull back on one whilst you’re doing that. Maybe 0.001% can break that rule, but I try and play by the bigger numbers!

Where does it leave me?

Well, currently I’m sitting in a situation where the UK Lake District rained for almost the entire window that I set aside for my goals this summer. It did kindly stop raining for one week and presented a glorious weather window, but I was in Norway falling off some hard cracks, so that didn’t work out quite like I planned! As it stands, I’m in the cardiovascular shape of my life (I don’t think I’ve ever felt as generally energetic or such good health in the last 10 years) but dropped off the top 5% in my climbing. What should I do now? Drop the running and take back my 5%? Push the running even further and risk giving up another margin…. My gut sense tells me I like climbing way more than running so I’ll stick with that for the moment, but next year will bring the 24hr challenge back to my doorstep and at some stage I’m going to have to play a fine balancing act again. Hopefully my family, co-workers and friends will still be talking to me.

Better pull my 5% finger out when I return….